New Diagnostic Architecture Overview

Diagnostics play a very important role in a programming language experience. It’s vital for developer productivity that the compiler can produce proper guidance in any situation, especially incomplete or invalid code.

In this blog post we would like to share a couple of important updates on improvements to diagnostics being worked on for the upcoming Swift 5.2 release. This includes a new strategy for diagnosing failures in the compiler, originally introduced as part of Swift 5.1 release, that yields some exciting new results and improved error messages.

The Challenge

Swift is a very expressive language with a rich type system that has many features like class inheritance, protocol conformances, generics, and overloading. Though we as programmers try our best to write well-formed programs, sometimes we need a little help. Luckily, the compiler knows exactly what Swift code is valid and invalid. The problem is how best to tell you what has gone wrong, where it happened, and how you can fix it.

Many parts of the compiler ensure the correctness of your program, but the focus of this work has been improving the type checker. The Swift type checker enforces rules about how types are used in source code, and it is responsible for letting you know when those rules are violated.

For example, the following code:

struct S<T> {

init(_: [T]) {}

}

var i = 42

_ = S<Int>([i!])

Produces the following diagnostic:

error: type of expression is ambiguous without more context

While this diagnostic points out a genuine error, it’s not helpful because it is not specific or actionable. This is because the old type checker used to guess the exact location of an error. This worked in many cases, but there were still numerous kinds of programming mistakes that users would write which it could not accurately identify. In order to address this, a new diagnostic infrastructure is in the works. Rather than guessing where an error occurs, the type checker attempts to “fix” problems right at the point where they are encountered, while remembering the fixes it has applied. This not only allows the type checker to pinpoint errors in more kinds of programs, it also allows it to surface more failures where previously it would simply stop after reporting the first error.

Type Inference Overview

Since the new diagnostic infrastructure is tightly coupled with the type checker, we have to take a brief detour and talk about type inference. Note that this is a brief introduction; for more details please refer to the compiler’s documentation on the type checker.

Swift implements bi-directional type inference using a constraint-based type checker that is reminiscent of the classical Hindley-Milner type inference algorithm:

- The type checker converts the source code into a constraint system, which represents relationships among the types in the code.

- A type relationship is expressed via a type constraint, which either places a requirement on a single type (e.g., it is an integer literal type) or relates two types (e.g., one is a convertible to the other).

- The types described in constraints can be any type in the Swift type system, including tuple types, function types, enum/struct/class types, protocol types, and generic types. Additionally, a type can be a type variable denoted as

$<name>. - Type variables can be used in place of any other type, e.g., a tuple type

($Foo, Int)involving the type variable$Foo.

The Constraint System performs three steps:

For diagnostics, the only interesting stages are Constraint Generation and Solving.

Given an input expression (and sometimes additional contextual information), the constraint solver generates:

- A set of type variables that represent an abstract type of each sub-expression

- A set of type constraints that describe the relationships between those type variables

The most common type of constraint is a binary constraint, which relates two types and is denoted as:

type1 <constraint kind> type2

Commonly used binary constraints are:

$X <bind to> Y- Binds type variable$Xto a fixed typeYX <convertible to> Y- A conversion constraint requires that the first typeXbe convertible to the secondY, which includes subtyping and equalityX <conforms to> Y- Specifies that the first typeXmust conform to the protocolY(Arg1, Arg2, ...) → Result <applicable to> $Function- An “applicable function” constraint requires that both types are function types with the same input and output types

Once constraint generation is complete, the solver attempts to assign concrete types to each of the type variables in the constraint system and form a solution that satisfies all of the constraints.

Let’s consider the following example function:

func foo(_ str: String) {

str + 1

}

For a human, it becomes apparent pretty quickly that there is a problem with the expression str + 1 and where that problem is located, but the inference engine can only rely on a constraint simplification algorithm to determine what is wrong.

As we have established previously, the constraint solver starts by generating constraints (see Constraint Generation stage) for str, 1 and +. Each distinct sub-element of the input expression, like str, is represented either by:

- a concrete type (known ahead of time)

- a type variable denoted with

$<name>which can assume any type that satisfies the constraints associated with it.

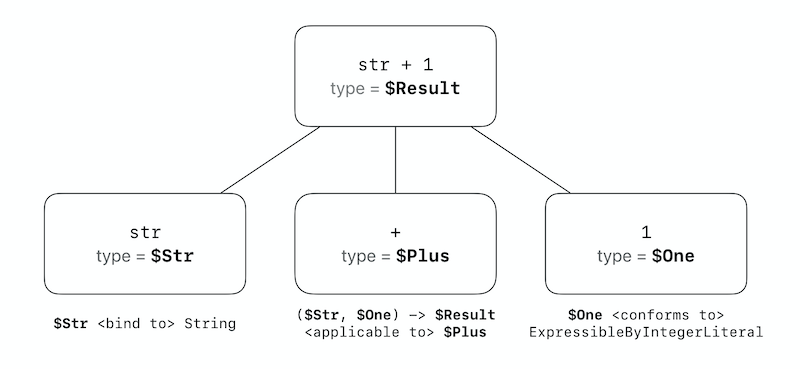

After the Constraint Generation stage completes, the constraint system for the expression str + 1 will have a combination of type variables and constraints. Let’s look at those now.

Type Variables

-

$Strrepresents the type of variablestr, which is the first argument in the call to+ -

$Onerepresents the type of literal1, which is the second argument in the call to+ -

$Resultrepresents the result type of the call to operator+ -

$Plusrepresents the type of the operator+itself, which is a set of possible overload choices to attempt.

Constraints

$Str <bind to> String- Argument

strhas a fixed String type.

- Argument

$One <conforms to> ExpressibleByIntegerLiteral- Since integer literals like

1in Swift could assume any type conforming to the ExpressibleByIntegerLiteral protocol (e.g.IntorDouble), the solver can only rely on that information at the beginning.

- Since integer literals like

$Plus <bind to> disjunction((String, String) -> String, (Int, Int) -> Int, ...)- Operator

+forms a disjoint set of choices, where each element represents the type of an individual overload.

- Operator

($Str, $One) -> $Result <applicable to> $Plus- The type of

$Resultis not yet known; it will be determined by testing each overload of$Pluswith argument tuple($Str, $One).

- The type of

Note that all constraints and type variables are linked with particular locations in the input expression:

The inference algorithm attempts to find suitable types for all type variables in the constraint system and test them against associated constraints. In our example, $One could get a type of Int or Double because both of these types satisfy the ExpressibleByIntegerLiteral protocol conformance requirement. However, simply enumerating through all of the possible types for each of the “empty” type variables in the constraint system is very inefficient since there could be many types to try when a particular type variable is under-constrained. For example, $Result has no restrictions, so it could potentially assume any type. To work around this problem, the constraint solver first tries disjunction choices, which allows the solver to narrow down the set of possible types for each type variable involved. In the case of $Result, this brings the number of possible types down to only the result types associated with overloads choices of $Plus instead of all possible types.

Now, it’s time to run the inference algorithm to determine types for $One and $Result.

A Single Round of Inference Algorithm Execution:

-

Let’s start by binding

$Plusto its first disjunction choice of(String, String) -> String -

Now the

applicable toconstraint could be tested because$Plushas been bound to a concrete type. Simplification of the($Str, $One) -> $Result <applicable to> $Plusconstraint ends up matching two function types($Str, $One) -> $Resultand(String, String) -> Stringwhich proceeds as follows:- Add a new conversion constraint to match argument 0 to parameter 0 -

$Str <convertible to> String - Add a new conversion constraint to match argument 1 to parameter 1 -

$One <convertible to> String - Equate

$ResulttoStringsince result types have to be equal

- Add a new conversion constraint to match argument 0 to parameter 0 -

-

Some of the newly generated constraints could be immediately tested/simplified e.g.

$Str <convertible to> Stringistruebecause$Stralready has a fixed type ofStringandStringis convertible to itself$Resultcould be assigned a type ofStringbased on equality constraint

-

At this point the only remaining constraints are:

$One <convertible to> String$One <conforms to> ExpressibleByIntegerLiteral

-

The possible types for

$OneareInt,Double, andString. This is interesting, because none of these possible types satisfy all of the remaining constraints;IntandDoubleboth are not convertible toString, andStringdoes not conform toExpressibleByIntegerLiteralprotocol -

After attempting all possible types for

$One, the solver stops and considers the current set of types and overload choices a failure. The solver then backtracks and attempts the next disjunction choice for$Plus.

We can see that the error location would be determined by the solver as it executes inference algorithm. Since none of the possible types match for $One it should be considered an error location (because it cannot be bound to any type). Complex expressions could have many more than one such location because existing errors result in new ones as the inference algorithm progresses. To narrow down error locations in situations like that, the solver would only pick solutions with the smallest possible number thereof.

At this point it’s more or less clear how error locations are identified, but it’s not yet obvious how to help the solver make forward progress in such scenarios so it can derive a complete solution.

The Approach

The new diagnostic infrastructure employs what we are going to call a constraint fix to try and resolve inconsistent situations where the solver gets stuck with no other types to attempt. The fix for our example is to ignore that String doesn’t conform to the ExpressibleByIntegerLiteral protocol. The purpose of a fix is to be able to capture all useful information about the error location from the solver and use that later for diagnostics. That is the main difference between current and new approaches. The former would try to guess where the error is located, where the new approach has a symbiotic relationship with the solver which provides all of the error locations to it.

As we noted before, all of the type variables and constraints carry information about their relationship to the sub-expression they have originated from. Such a relation combined with type information makes it straightforward to provide tailored diagnostics and fix-its to all of the problems diagnosed via the new diagnostic framework.

In our example, it has been determined that the type variable $One is an error location, so the diagnostic can examine how $One is used in the input expression: $One represents an argument at position #2 in call to operator +, and it’s known that the problem is related to the fact that String doesn’t conform to ExpressibleByIntegerLiteral protocol. Based on all this information it’s possible to form either of the two following diagnostics:

error: binary operator '+' cannot be applied to arguments 'String' and 'Int'

with a note about the second argument not conforming to the ExpressibleByIntegerLiteral protocol, or the simpler:

error: argument type 'String' does not conform to 'ExpressibleByIntegerLiteral'

with the diagnostic referring to the second argument.

We picked the first alternative and produce a diagnostic about the operator and a note for each partially matching overload choice. Let’s take a closer look at the inner workings of the described approach.

Anatomy of a Diagnostic

When a constraint failure is detected, a constraint fix is created that captures information about a failure:

- The kind of failure that occurred

- The location in the source code where the failure came from

- The types and declarations involved in the failure

The constraint solver accumulates these fixes. Once it arrives at a solution, it looks at the fixes that were part of a solution and produces actionable errors or warnings. Let’s take a look at how this all works together. Consider the following example:

func foo(_: inout Int) {}

var x: Int = 0

foo(x)

The problem here is related to an argument x which cannot be passed as an argument to inout parameter without an explicit &.

Let’s now look at the type variables and constraints for this constraint system.

Type Variables

There are three type variables:

$X := Int

$Foo := (inout Int) -> Void

$Result

Constraints

The three type variables have the following constraint:

($X) -> $Result <applicable to> $Foo

The inference algorithm is going to try and match ($X) -> $Result to (inout Int) -> Void, which results in the following new constraints:

Int <convertible to> inout Int

$Result <equal to> Void

Int cannot be converted into inout Int, so the constraint solver records the failure as a missing & and ignores the <convertible to> constraint.

With that constraint ignored, the remainder of the constraint system can be solved. Then the type checker looks at the recorded fixes and emits an error that describes the problem (a missing &) along with a Fix-It to insert the &:

error: passing value of type 'Int' to an inout parameter requires explicit '&'

foo(x)

^

&

This example had a single type error in it, but this diagnostics architecture can also account for multiple distinct type errors in the code. Consider a slightly more complicated example:

func foo(_: inout Int, bar: String) {}

var x: Int = 0

foo(x, "bar")

While solving this constraint system, the type checker will again record a failure for the missing & on the first argument to foo. Additionally, it will record a failure for the missing argument label bar. Once both failures have been recorded, the remainder of the constraint system is solved. The type checker then produces errors (with Fix-Its) for the two problems that need to be addressed to fix this code:

error: passing value of type 'Int' to an inout parameter requires explicit '&'

foo(x)

^

&

error: missing argument label 'bar:' in call

foo(x, "bar")

^

bar:

Recording every specific failure and then continuing on to solve the remaining constraint system implies that addressing those failures will produce a well-typed solution. That allows the type checker to produce actionable diagnostics, often with fixes, that lead the developer toward correct code.

Examples Of Improved Diagnostics

Missing label(s)

Consider the following invalid code:

func foo(answer: Int) -> String { return "a" }

func foo(answer: String) -> String { return "b" }

let _: [String] = [42].map { foo($0) }

Previously, this resulted in the following diagnostic:

error: argument labels '(_:)' do not match any available overloads`

This is now diagnosed as:

error: missing argument label 'answer:' in call

let _: [String] = [42].map { foo($0) }

^

answer:

Argument-to-Parameter Conversion Mismatch

Consider the following invalid code:

let x: [Int] = [1, 2, 3, 4]

let y: UInt = 4

_ = x.filter { ($0 + y) > 42 }

Previously, this resulted in the following diagnostic:

error: binary operator '+' cannot be applied to operands of type 'Int' and 'UInt'`

This is now diagnosed as:

error: cannot convert value of type 'UInt' to expected argument type 'Int'

_ = x.filter { ($0 + y) > 42 }

^

Int( )

Invalid Optional Unwrap

Consider the following invalid code:

struct S<T> {

init(_: [T]) {}

}

var i = 42

_ = S<Int>([i!])

Previously, this resulted in the following diagnostic:

error: type of expression is ambiguous without more context

This is now diagnosed as:

error: cannot force unwrap value of non-optional type 'Int'

_ = S<Int>([i!])

~^

Missing Members

Consider the following invalid code:

class A {}

class B : A {

override init() {}

func foo() -> A {

return A()

}

}

struct S<T> {

init(_ a: T...) {}

}

func bar<T>(_ t: T) {

_ = S(B(), .foo(), A())

}

Previously, this resulted in the following diagnostic:

error: generic parameter ’T’ could not be inferred

This is now diagnosed as:

error: type 'A' has no member 'foo'

_ = S(B(), .foo(), A())

~^~~~~

Missing Protocol Conformance

Consider the following invalid code:

protocol P {}

func foo<T: P>(_ x: T) -> T {

return x

}

func bar<T>(x: T) -> T {

return foo(x)

}

Previously, this resulted in the following diagnostic:

error: generic parameter 'T' could not be inferred

This is now diagnosed as:

error: argument type 'T' does not conform to expected type 'P'

return foo(x)

^

Conditional Conformances

Consider the following invalid code:

extension BinaryInteger {

var foo: Self {

return self <= 1

? 1

: (2...self).reduce(1, *)

}

}

Previously, this resulted in the following diagnostic:

error: ambiguous reference to member '...'

This is now diagnosed as:

error: referencing instance method 'reduce' on 'ClosedRange' requires that 'Self.Stride' conform to 'SignedInteger'

: (2...self).reduce(1, *)

^

Swift.ClosedRange:1:11: note: requirement from conditional conformance of 'ClosedRange<Self>' to 'Sequence'

extension ClosedRange : Sequence where Bound : Strideable, Bound.Stride : SignedInteger {

^

SwiftUI Examples

Argument-to-Parameter Conversion Mismatch

Consider the following invalid SwiftUI code:

import SwiftUI

struct Foo: View {

var body: some View {

ForEach(1...5) {

Circle().rotation(.degrees($0))

}

}

}

Previously, this resulted in the following diagnostic:

error: Cannot convert value of type '(Double) -> RotatedShape<Circle>' to expected argument type '() -> _'

This is now diagnosed as:

error: cannot convert value of type 'Int' to expected argument type 'Double'

Circle().rotation(.degrees($0))

^

Double( )

Missing Members

Consider the following invalid SwiftUI code:

import SwiftUI

struct S: View {

var body: some View {

ZStack {

Rectangle().frame(width: 220.0, height: 32.0)

.foregroundColor(.systemRed)

HStack {

Text("A")

Spacer()

Text("B")

}.padding()

}.scaledToFit()

}

}

Previously, this used to be diagnosed as a completely unrelated problem:

error: 'Double' is not convertible to 'CGFloat?'

Rectangle().frame(width: 220.0, height: 32.0)

^~~~~

The new diagnostic now correctly points out that there is no such color as systemRed:

error: type 'Color?' has no member 'systemRed'

.foregroundColor(.systemRed)

~^~~~~~~~~

Missing arguments

Consider the following invalid SwiftUI code:

import SwiftUI

struct S: View {

@State private var showDetail = false

var body: some View {

Button(action: {

self.showDetail.toggle()

}) {

Image(systemName: "chevron.right.circle")

.imageScale(.large)

.rotationEffect(.degrees(showDetail ? 90 : 0))

.scaleEffect(showDetail ? 1.5 : 1)

.padding()

.animation(.spring)

}

}

}

Previously, this resulted in the following diagnostic:

error: type of expression is ambiguous without more context

This is now diagnosed as:

error: member 'spring' expects argument of type '(response: Double, dampingFraction: Double, blendDuration: Double)'

.animation(.spring)

^

Conclusion

The new diagnostic infrastructure is designed to overcome all of the shortcomings of the old approach. The way it’s structured is intended to make it easy to improve/port existing diagnostics and to be used by new feature implementors to provide great diagnostics right off the bat. It shows very promising results with all of the diagnostics we have ported so far, and we are hard at work porting more every day.

Questions?

Please feel free to post questions about this post on the associated thread on the Swift forums.