Whole-Module Optimization in Swift 3

Whole-module optimization is an optimization mode of the Swift compiler. The performance win of whole-module optimization heavily depends on the project, but it can be up to two or even five times.

Whole-module optimization can be enabled with the -whole-module-optimization (or -wmo) compiler flag, and in Xcode 8 it is turned on by default for new projects.

Also the Swift Package Manager compiles with whole-module optimizations in release builds.

So what is it about? Let’s first look at how the compiler works without whole-module optimizations.

Modules and how to compile them

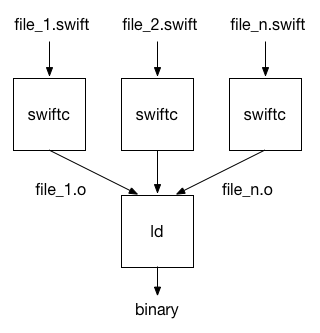

A module is a set of Swift files. Each module compiles down to a single unit of distribution—either a framework or an executable. In single-file compilation (without -wmo) the Swift compiler is invoked for each file in the module separately. Actually, this is what happens behind the scenes. As a user you don’t have to do this manually. It is automatically done by the compiler driver or the Xcode build system.

After reading and parsing a source file (and doing some other stuff, like type checking), the compiler optimizes the Swift code, generates machine code and writes an object file. Finally the linker combines all object files and generates the shared library or executable.

In single-file compilation the scope of the compiler’s optimizations is just a single file. This limits cross-function optimizations, like function inlining or generic specialization, to functions which are called and defined in the same file.

Let’s look at an example. Let’s assume one file of our module, named utils.swift, contains a generic utility data structure Container<T> with a method getElement and this method is called throughout the module, for example in main.swift.

main.swift:

func add (c1: Container<Int>, c2: Container<Int>) -> Int {

return c1.getElement() + c2.getElement()

}

utils.swift:

struct Container<T> {

var element: T

func getElement() -> T {

return element

}

}

When the compiler optimizes main.swift it does not know how getElement is implemented. It just knows that it exists. So the compiler generates a call to getElement. On the other hand, when the compiler optimizes utils.swift, it does not know for which concrete types the function is called. So it can only generate the generic version of the function which is much slower than code which is specialized for a concrete type.

Even the simple return statement in getElement needs a lookup in the type’s metadata to figure out how to copy the element. It could be a simple Int, but it could also be a larger type, even involving some reference counting operations. The compiler just doesn’t know.

Whole-module optimization

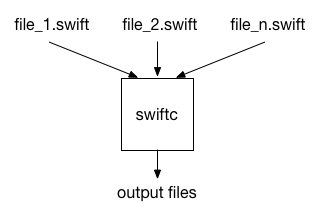

With whole-module optimization the compiler can do a lot better. When compiling with the -wmo option, the compiler optimizes all files of a module as a whole.

This has two big advantages. First, the compiler sees the implementation of all functions in a module, so it can perform optimizations like function inlining and function specialization. Function specialization means that the compiler creates a new version of a function which is optimized for a specific call-context. For example, the compiler can specialize a generic function for concrete types.

In our example, the compiler produces a version of the generic Container which is specialized for the concrete type Int.

struct Container {

var element: Int

func getElement() -> Int {

return element

}

}

Then the compiler can inline the specialized getElement function into the add function.

func add (c1: Container<Int>, c2: Container<Int>) -> Int {

return c1.element + c2.element

}

This compiles down to just a few machine instructions. That’s a big difference compared to the single-file code where we had two calls to the generic getElement function.

Function specialization and inlining across files are just examples of optimizations the compiler is able to do with whole-module optimizations. Even if the compiler decides not to inline a function, it helps a lot if the compiler sees the implementation of the function. For example it can reason about its behavior regarding reference counting operations. With this knowledge the compiler is able to remove redundant reference counting operations around a function call.

The second important benefit of whole-module optimization is that the compiler can reason about all uses of non-public functions. Non-public functions can only be used within the module, so the compiler can be sure to see all references to such functions. What can the compiler do with this information?

One very basic optimization is the elimination of so called “dead” functions and methods. These are functions and methods which are never called or otherwise used. With whole-module optimizations the compiler knows if a non-public function or method is not used at all, and if that’s the case it can eliminate it. So why would a programmer write a function, which is not used at all? Well, this is not the most important use case for dead function elimination. Often functions become dead as a side-effect of other optimizations.

Let’s assume that the add function is the only place where Container.getElement is called. After inlining getElement, this function is not used anymore, so it can be removed. Even if the compiler decides to not inline getElement, the compiler can remove the original generic version of getElement, because the add function only calls the specialized version.

Compile time

With single-file compilation the compiler driver starts the compilation for each file in a separate process, which can be done in parallel. Also, files which were not modified since the last compilation don’t need to be recompiled (assuming all dependencies are also unmodified). That’s called incremental compilation. All this saves a lot of compile time, especially if you only make a small change. How does this work in whole-module compilation? Let’s look at how the compiler works in whole-module optimization mode in more detail.

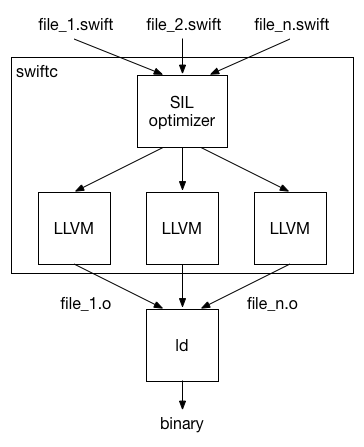

Internally the compiler runs in multiple phases: parser, type checking, SIL optimizations, LLVM backend.

Parsing and type checking is very fast in most cases, and we expect it to get even faster in subsequent Swift releases. The SIL optimizer (SIL stands for “Swift Intermediate Language”) performs all the important Swift-specific optimizations, like generic specialization, function inlining, etc. This phase of the compiler typically takes about one third of the compilation time. Most of the compilation time is consumed by the LLVM backend which runs lower-level optimizations and does the code generation.

After performing whole-module optimizations in the SIL optimizer the module is split again into multiple parts. The LLVM backend processes the split parts in multiple threads. It also avoids re-processing of a part if that part didn’t change since the previous build. So even with whole-module optimizations, the compiler is able to perform a big part of the compilation work in parallel (multi-threaded) and incrementally.

Conclusion

Whole-module optimization is a great way to get maximum performance without having to worry about how to distribute Swift code across files in a module. If optimizations, like described above, kick in at a critical code section, performance can be up to five times better than with single-file compilation. And you get this high performance with much better compile times than typical to monolithic whole-program optimization approaches.